I wrote at the end of the previous entry that I would “think about it a bit more,” so I tried hard to think it over in my own way afterward. However, with my limited ability, I couldn’t reach any particularly new insights. I did feel, though, that there are still many people who mistakenly believe that hate speech, like that of the “Zaitokukai,” is free speech.

Hate has nothing to do with the ‘debate between left and right

Can hate ‘demonstrations’ really be called ‘freedom of speech’?

I’ve said it before and will keep saying it as many times as necessary: Discrimination (hate speech) is not “freedom of speech.” It is simply an act of human rights violation, and in most developed countries, it even constitutes a criminal offense.

Regarding the status of permanent residency for Korean (North and South) residents in Japan (as part of post-colonial policies), as well as the future of immigration policies, a wide range of commentators, from conservatives to leftists, continue to present various opinions. Debates persist not only between the right and left but even within conservative and leftist circles, where sharp disagreements occur. The same goes for discussions on Asian diplomacy. If there is a legitimate reason to protest against South Korea, China, or North Korea, then go ahead (freedom of speech). No one believes these countries are perfect, faultless utopias.

However, hate speech (discrimination) has absolutely nothing to do with these kinds of debates. It is something that all commentators, from conservatives to leftists, should unanimously condemn and work to overcome and eradicate from society. Because hate speech is such a socially harmful presence, even Prime Minister Abe had no choice but to openly criticize the “Zaitokukai.” For racists to expect to be treated as “fellow participants in this debate,” alongside everyone from conservatives to leftists, is nothing short of astonishingly audacious.

No one has the ‘right to discriminate’ against others

If discrimination were considered free speech, then its expression would become a human right, which would create a logical contradiction of a “right to violate human rights.” You may have heard phrases like “freedom comes with responsibility” or “public welfare.” These do not mean “individuals should be sacrificed for the nation,” of course. Rather, as long as each person’s human rights are protected, individuals must not infringe upon the rights of others and can exercise their rights within that boundary.

This is why the phrase “the right to violate human rights” is a logical contradiction. Our country’s constitution expresses this concept as follows: “The freedoms and rights guaranteed to the people by this Constitution shall be maintained by the constant endeavor of the people, who shall refrain from any abuse of these freedoms and rights and shall always be responsible for utilizing them for the public welfare” (Article 12).

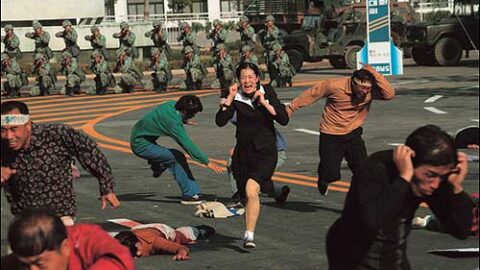

This is an extremely simple matter that hardly requires explanation. We have the freedom to move anywhere within Japan, but what if someone were to claim “I have the right to move freely” and then forcibly enter someone else’s home or demand an interview? Or, should we consider it a “right” for someone to verbally attack another person or group just because they don’t like them? Is it a “right” to barge into a Korean community while shouting “Kill all Koreans!”? Let me say it again—when you think about it, it’s really quite simple.

When “Words” Become a Crime

I imagine that some people, perhaps out of misunderstanding, feel discomfort or hesitation at the idea that beliefs or words—no matter how discriminatory—could be considered criminal or seen as something that society should work to overcome. I believe many of these individuals mean well. However, under our country’s Penal Code, there are already provisions, such as for defamation (Article 230) and insult (Article 231), where “words” themselves can be considered criminal. Why do they become criminal? Because those words infringe on the rights of others.

Additionally, what distinguishes murder (Article 199) from bodily injury resulting in death (Article 205) is the presence or absence of intent to kill—a matter of internal mindset. The concept of “intent,” which is a crucial factor in many legal provisions, already considers one’s inner state as an element of criminal responsibility, and few people would likely dispute this. This is because doing so ensures that human rights are protected more fairly.

While almost no one opposes the existence of defamation laws, relatively many people hesitate to support the idea of overcoming and eliminating hate speech and the groups that spread it (whether through legal or social means). Why is this? I believe it’s a matter of imagination. With defamation, it’s relatively easy to imagine oneself or a loved one as the victim, envisioning what that situation would look like and understanding the need for regulations that protect one’s rights.

However, in the case of hate speech, it tends to feel like “someone else’s problem” rather than a human rights violation that personally resonates. People may perceive it more as a “social phenomenon” in general. As the overwhelming majority in Japan, we Japanese wouldn’t feel particularly hurt if a foreigner in Japan said, “Oh, Japanese people are stupid.” Perhaps that’s why some people view hate speech directed at minorities as something similar.

However, in reality, this is a serious issue. The fear and anxiety experienced by people who make up only 1% to, at most, 3% of the population when confronted with hate speech spread by the overwhelming majority of Japanese is something difficult to imagine. Precisely because we are Japanese, we should prioritize addressing this problem first and foremost.

The Presence or Absence of Guilt (Intent) is Judged by the Outward Appearance of Actions

Additionally, it’s worth noting that defendants often claim in murder trials that they “had no intent to kill,” asserting instead that it was a case of bodily injury resulting in death. However, in extreme cases, such as repeatedly stabbing someone in the heart, it’s inconceivable that “no intent to kill” would be accepted. Naturally, no matter how much it concerns “internal intent,” its determination is ultimately based on an assessment of outward actions.

In the same way, racists often insist that they “have no intent to discriminate.” However, asserting something like “Koreans should go back to their country!” clearly targets a specific ethnic group for exclusion, and it’s equally inconceivable that this would not be recognized as discrimination. Discrimination (a human rights violation) is ultimately judged by the outward appearance of actions or the effects those actions produce. This is why it’s essential to understand the need to focus on the “words” themselves as outward expressions.

Definition of Discriminatory Exclusionism (Racism)

So, specifically, what kinds of words and actions constitute discrimination based on race or nationality? Within leftist circles, some express the opinion that even broadly nationalist conservative ideologies should be considered discriminatory. This viewpoint is understandable; however, if we were to include areas that are still quite contentious in defining hate speech (a crime), it could make the scope of what constitutes a crime ambiguous. Additionally, there is a risk that the confrontation between hate speech and counter-speech might be misinterpreted as merely a “difference of opinion.”

For now, I believe it’s appropriate to limit the definition strictly to blatantly obvious hate speech that leaves no room for doubt, such as “Kill the Koreans” or “Throw the Koreans into the Sea of Japan.” Such clear-cut hate speech should always be included in the criteria. Rather than sharing my personal opinions or leftist viewpoints on this, I’d like to present some excerpts from the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination as an internationally established, objective standard for defining racial discrimination.

“Racial discrimination” refers to any distinction, exclusion, restriction, or preference based on race, color, descent, or national or ethnic origin that has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment, or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, or any other field of public life.

From Article 1 of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1969)

All propaganda and organizations based on ideas or theories of the superiority of one race, color, or group of persons of ethnic origin, as well as all propaganda and organizations that attempt to justify or promote racial hatred and racial discrimination (in any form).

From Article 4 of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1969)

All dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred, incitement to racial discrimination, and all acts of violence or incitement to such acts against any group of persons of different race, color, or ethnic origin, as well as activities based on racism (Article 4).

From Article 4 of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1969)

※The term “descent” may sound unfamiliar, but it refers to collective classifications based on lineage or place of birth. In traditional Japanese, “monchi” (social class or lineage) is a close equivalent. This means that, according to international standards, discrimination against Burakumin or Okinawans is considered racial discrimination.

※Regarding distinctions based on “nationality,” since human rights are “the rights of human beings” and not exclusively “the rights of citizens,” the human rights recognized by the Constitution and other legal frameworks are generally granted to all individuals, including those of foreign nationality. Rights that, by their nature, are not applicable to non-citizens (e.g., the right to renounce Japanese nationality, as in Article 22 of the Constitution) are excluded, but this exclusion is not considered discriminatory (see Article 1, Paragraph 2 of this Convention, and prevailing constitutional interpretations and case law).

※Special assistance aimed at overcoming disadvantages faced by specific vulnerable or minority groups (so-called affirmative action) is not considered discrimination (Article 1, Paragraph 4 of the Convention). However, it must not constitute a permanent “granting of rights” but rather remain as temporary assistance or preferential measures.

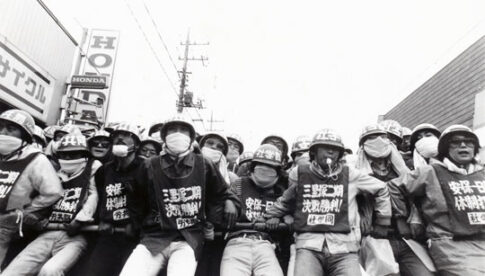

Are Counter-Protesters (Opponents of Racial Discrimination) Doing the “Same Thing”?

Finally, I considered the comment previously mentioned in AA’s post, which questioned, “Aren’t the counter-protesters doing the same thing as the hate group?”

I’m not entirely sure what AA meant by calling it “the same.” There are many kinds of people on the counter-protester side, but let’s consider this broadly, including all those involved. Furthermore, rather than focusing solely on actions taken on the day of the counter-protest, I’ve expanded the scope to include various activities and considered whether similar actions or behaviors might indeed be comparable.

With this in mind, I tried to imagine examples where, if counter-protesters engaged in such actions, it would indeed be fair to say they were no different from the “Zaitokukai” and merely held a “difference of opinion” (birds of a feather).

I tried to imagine a “left-wing version of Zaitokukai,” and this is generally the kind of thing they do. Fortunately, as far as I know, no group is engaging in actions similar to those of Zaitokukai. It’s possible that I’m simply unaware, but if even a small group were to act in such a manner, it would become a huge issue. So I think such people probably don’t exist. It really isn’t the “same thing.”

As I wrote this, I realized that if such actions were actually carried out, they would indeed have a significant “impact.” However, unlike Zaitokukai being allowed to harass Korean communities unchecked, the police would likely rush over immediately, looking pale, and arrest everyone involved. Even so, the “impact” would remain. But still—no matter how strongly I (or we) might protest against the policies of the U.S. military or government, I could never engage in discrimination based on race or nationality by saying something like “Americans are the enemy.”

Encouraging Open Dialogue Within the Counter-Movement

Even if it’s not as extreme as the examples above, there are always exceptions. I’ve heard that some right-wing individuals stopped attending Zaitokukai “demonstrations” because they were disgusted by the excessive discriminatory language. Conversely, there are also people on the counter-protest side who shout things that make one think, “Is that really appropriate for someone opposing discrimination?”

In this context, the “Shibaki-tai” often comes under fire, but even before their emergence, there were always a few people who behaved in that manner. The fact is, these issues were left unaddressed, and there was no open discussion at the time. So now, trying to suddenly question this as a “problem unique to the Shibaki-tai” feels a bit misplaced to me.

The real issue is whether those who participate in counter-protests—across individual, group, or organizational lines—can foster an open atmosphere where everyone can discuss these matters freely. If that’s possible, I believe these issues can certainly be overcome, especially with the internet as a tool for dialogue. I do understand, however, that this ideal hasn’t yet been fully realized. Regarding the Shibaki-tai, there seems to be some widespread misunderstanding (or misinformation) that may cause trouble for them and others involved, so I plan to address this in more detail at a later date.

By the way, this might be a bit off-topic, but yesterday on Twitter, I saw someone do something that was brave, in a way: they “praised” a leftist by comparing them to the Emperor. Naturally, the person being “praised” was furious. That’s like giving a Yasukuni Shrine charm to someone who opposes Yasukuni, or telling a right-winger to tear up the national flag. It’s not only a bit rude, but telling someone to be happy about it is essentially the same as asking them to abandon all their beliefs.

Yet, this person didn’t realize their rudeness and, despite the anger directed at them, stubbornly insisted, “For me, it’s a compliment, so it’s fine.” As a result, they were getting criticized by a few people. I tried to smooth things over without adding fuel to the fire, but maybe I was too subtle (laugh), as I ended up being mistaken for one of the leftists criticizing them. And then, at that point, I think they started saying something about idealism or whatever.

But well, it can’t be helped. Idealism exists, and realism is there to help make it a reality. If we lose our ideals, it’s over. No matter how “effective” certain actions may be, I simply can’t become “the same” as Zaitokukai.

Reference Links

- Commemorating the Release of Chairman Sakurai – “The Sakurai Makoto of Korea”

- On the Essence of the Rhetoric of the ‘Ordinary Person’

- Support the Arrested Protesters from the June 16 Shin-Okubo Counter-Action – Start by Raising Your Voice: ‘These Arrests Are Unjust’

- Words Can Kill: Online Bullying and Hate Mobs

- What is Hate Speech Regulation?(Miki Hideo Law Office)

- Full Text of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination(Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

- I attended a seminar on the Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

Donations are made in Japanese yen. 300 yen is approximately 2 USD.

Donations are made in Japanese yen. 300 yen is approximately 2 USD.

Leave a Reply