Kousuke Soka self-introduction

Summary

- Claims to be a “leftist,” but this is highly questionable.

- Has been told by genuine leftists, “Don’t call yourself a leftist!” (multiple times).

∟ To avoid this, now often refers to themselves as a “former leftist.” - Doesn’t understand terms like “alienation” or “reification” even after reading leftist books.

- Is even more baffled by trendy modern philosophies.

- But can sing “The Internationale.”

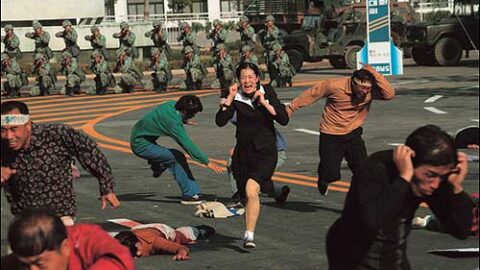

- Gets excited at the sight of police gathered in groups.

- A former activist with three arrests (all charges dropped).

- Often stops in front of the helmet section in hardware stores.

- Feels a murderous urge when someone reveals the source of their “knowledgeable” speech.

- Has experience starting debates in the comment sections of other people’s journals.

∟ Truly sorry about this. Never again. Let’s all be careful. - Once tried to read Das Kapital but gave up when they couldn’t figure out the length of a woolen fabric bolt.

Foolish leftists of the world, stop pretending to understand and unite!

The Origin of the Pen Name “Kosuke”

When I first began expressing myself online, the name “Kosuke” (耕助) naturally came to mind, combining the ideas of “cultivating” (耕す) and “helping” (助ける). Above all, it was inspired by the Sanrizuka Struggle. However, it wasn’t only that. The name was also chosen with the hope that this online persona could serve as a source of support for all the people across the world who are engaged in cultivating various things.

Career as a Former Leftist Activist

I was formerly an activist affiliated with the Battle Flag Communist League (BFCL Senki-ha faction ) . Although I was never a member of the main league itself, I belonged to its subordinate organization, the Communist Youth League (KIM). I served as a branch captain in mass organizations such as the Socialist Students League (Shagakudo) and the Workers’ Joint Struggle Council (Rokyoto), and participated in the district headquarters meetings of the Battle Flag faction.

My activism spanned from the early to late 1980s. The primary focus of my activities included: supporting South Korea’s democratization movement, Japan-South Korea solidarity struggles, the fight to prevent Kim Dae-jung’s execution, condemning the Gwangju Massacre, opposing Chun Doo-hwan’s visit to Japan, anti-Narita Airport struggles, the “One-Week Battle to Block Jet Fuel Transport,” the Narita Irrigation Water Destruction Battle at Henda, anti-war and anti-nuclear struggles of the 1980s, the Enterprise blockade in Yokosuka, the Tokiwa Bridge battle against Reagan’s visit to Japan, solidarity with the Iranian revolution in the Middle East, and support for the Nicaraguan revolution in Central America. I was arrested twice (both times resulting in deferred prosecution).

… However, after becoming “Kosuke Soka,” something completely absurd happened related to the Narita Struggle. While (seriously! truly!) doing absolutely nothing and merely sitting in the waiting area of a courthouse (following staff instructions, no less), a Public Security officer suddenly entered and said, “Come with me.” Having no choice, I went along with several others, only to be shoved into a transport vehicle. It was then that I realized: “Wait… was I just arrested? Why?”

In the end, I was released after 48 hours. Apparently, their policy was to arrest everyone present in the courthouse at that time. It’s baffling how casually they can alter people’s lives like that! And so, with this incident, I cheerfully achieved the milestone of “three arrests.” What an ending to the story.

On Self-Development During High School

Family Background, etc.

I attended a nationally renowned high school known for its academic rigor. In middle school, my acceptance into such a prestigious school was considered nothing short of a “miracle” by those familiar with my usual grades (I thought so too).

During my high school years, I might have appeared to others as a stoic literary youth, often engrossed in reading Akutagawa or Dazai during class. However, I personally felt like a typical child of ordinary means and, if anything, closer to being a struggling student. My family was relatively poor, but thanks to the love and efforts of my parents, I grew up without feeling particularly miserable about my circumstances. I am deeply grateful to them for that.

The Death of a Classmate

One of the most unforgettable events from this time was the death of a classmate who had been bullied. He was hospitalized and later died from an “unknown cause.” Although I was not close to him, he was the kind of person who happily took care of his younger sister with polio while attending school, a fan of Eikichi Yazawa, and, in short, just an ordinary high school student. I had witnessed the bullying but never did anything to intervene.

The day I returned from his funeral, I broke down and cried, blaming myself. I continued crying every night for about a week. The day after the funeral, I clenched my fists when I saw members of the bullying group laughing hysterically while mocking his sister’s polio. My anger wasn’t directed at them but at myself for being powerless to confront them. Oddly enough, I started to see them as pitiable people rather than individuals I should hate.

Eventually, I became the target of their bullying. After his death, they needed a new “errand boy” to replace him. When I refused their demands, I was beaten severely. They kicked me in the face as I lay on the ground, leaving my face swollen. My school cap was stomped on, and my shoes were thrown away. This became a daily occurrence. Yet I continued to resist.

Being subjected to violence myself gave me a strange sense of liberation. I wondered what I had been so afraid of, what I had been hesitating over. The people who were beating me began to appear more and more pitiful. This growing sense of pity made the ordeal far less painful than one might imagine. I even felt relieved that I was on the receiving end of violence rather than inflicting it. My refusal to show fear, standing tall and looking at them with pity in my eyes, seemed to infuriate them further, escalating their violence.

Over time, I found myself genuinely wanting to save them, to help them realize, as human beings, what they had done to the classmate who had died. Yet I knew there was nothing I could do. These people, who had become like beasts, are likely still out there somewhere in society today, living seemingly normal lives—marrying, doting on their children, and even being considered “good people” at times. They probably wear the guise of ordinary human beings now. At the very least, I’m certain they didn’t become leftists.

In any case, it was during this period that certain feelings took root within me: resentment toward people who treat others as less than human, exploit others without hesitation, or look down on others using violence, power, or money; aversion to insufferable elitism; empathy for the weak who are oppressed without cause, whether human or otherwise; and guilt over my own inability to take action.

What I Gained from My Experience as a Leftist Activist

Acquiring a “Dialectical Way of Thinking” (?)

One valuable thing I gained was the idea that in human relationships, unless I (the thesis) change, I cannot hope to change others (the antithesis).

In the organization, I was taught that trying to change others only in ways that suit your own sense of correctness or convenience leads nowhere. Instead, it is crucial to acknowledge the other person’s life experiences and struggles, learn from them, and grow yourself. Only then can you and the other person explore a shared direction (aufheben). This, they said, is the essence of mass movements and mass organization.

However, this notion itself is a thesis. Then comes the antithesis: “Mass movements are not a game. Without using techniques, rhetoric, or sometimes even sophistry and strategy, one risks being destroyed in the world of politics.” Finally, these ideas are also subjected to further aufheben (sublation).

This way of thinking and the practical experience I gained can be applied broadly, from management and human relationships to family matters. Reflecting on my high school days and the bullying group, I now think that if I had wanted to change them, it wouldn’t have been enough to see them as villains and myself as righteous. It would have required me to reflect on and transform my own subjectivity first.

Becoming Resistant to Scams

I am naturally a person who finds it hard to distance myself from others or outright reject them. I also tend to listen to people with an initial sense of trust, which makes me susceptible to scams.

However, I learned this simple principle: a nation’s wealth—its value—is generated only through labor. To increase value, one must increase productivity through labor. A nation’s currency is nothing more than a representation of the aggregate value of its products.

If one wants to acquire value without labor, there are only three ways:

- Exploit the labor of others on a massive scale by becoming a capitalist.

- Capitalize on supply-demand imbalances to sell goods at prices above their intrinsic value.

- Invest in pre-existing value in the market (i.e., gamble).

Value cannot be increased without labor; everything else is gambling—a system where equally gathered value is redistributed unequally according to game-like rules. Fraudulent schemes are essentially gambles where the rules are unfair or heavily skewed in favor of the organizers.

Knowing this allows even someone like me—timid and prone to being deceived—to instantly recognize a fraudulent scheme and confront the perpetrators. Of course, those who can outright dismiss others’ claims from the start (and I mean this without irony) might not need such a framework.

Educational Background

Graduated from Yasumoto Music Kindergarten, Kyoto Municipal Fukakusa Elementary School, Kyoto Municipal Daigo Junior High School, and Rakunan High School. Entered Hanazono University (Faculty of Literature, Department of Social Welfare) but dropped out to focus on activism. After leaving organizational activities, I worked while completing my degree at Ritsumeikan University (Faculty of Law, Department of Law).

[Sponsor Ad]

Donations are made in Japanese yen. 300 yen is approximately 2 USD.

Donations are made in Japanese yen. 300 yen is approximately 2 USD.