This was a learning seminar I attended in March, but I completely forgot to publish it! (ノ≧ڡ≦)

Recently, I’ve been seeing discussions about the upcoming South Korean presidential election, so now feels like the right time to share this.

I had some basic knowledge from this Commons article, but I was concerned about developments afterward. South Korea’s prosecutorial reform faced fierce resistance but managed to be completed, which is good news for now. However, it might still be too soon to feel entirely secure until the changes take root.

- 1 From the Learning Session Announcement

- 2 Introduction

- 3 Ⅰ. What Deep-Rooted Corruption Did the Moon Administration Aim to Eliminate?—Democratization as the Aspiration of the Candlelight Revolution

- 3.1 1. Breaking Political and Economic Collusion and Democratizing the Economy

- 3.2 2. Political Democratization—Prosecutorial Reform as Moon's Top Policy Promise

- 3.3 3. Why Did the Conflict Occur?

- 3.4 4. Act Two of the Conflict—The Clash Between Justice Minister Choo Mi-ae and Prosecutor General Yoon Seok-yeol

- 3.5 5. Developments in 2021

- 4 Ⅱ. Remaining External Deep-Rooted Corruption

- 5 For reference: South Korean Movie "The King"

From the Learning Session Announcement

〇 President Moon Jae-in, Chosen by the Candlelight Citizens

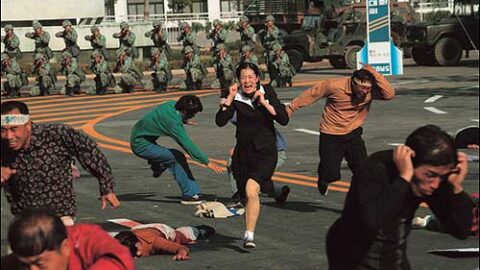

From the winter of 2016 to the following spring, citizens burdened by extreme wealth inequality, unemployment, low wages, tuition fees, and other issues lit 17 million candles. This movement not only impeached (removed) President Park Geun-hye from office but also reflected a recognition that the urgent problems faced by individuals could not be resolved without establishing a democratic government. As a result, Moon Jae-in, seen as the most representative of democratic values, was elected president.

The candlelight citizens passionately chanted, “Sovereignty resides with the people.”

〇 President Moon, Self-Proclaimed “Child of the Candlelight Citizens”

Amid resistance and backlash from entrenched vested interests both within and outside the National Assembly and from conservative media, President Moon pushed for new and revised laws to establish true democracy.

→ Prosecutorial reform, judicial reform, economic democratization…

〇 Moon Administration VS the Prosecution

Prosecutorial reform was the centerpiece of the Candlelight Citizens’ demand to eliminate deep-seated corruption. In response, the prosecution launched counterattacks, supported by conservative media.

Japanese-language newspapers uncritically echoed the refrain, “According to Korean media…”

→ How reliable is this information?

These reports ignored the historical context behind the conflicts and predominantly blamed the president. Readers accepted these narratives uncritically, which were further distorted, amplified, and spread through irresponsible TV commentary and online discourse.

What is truly happening in neighboring South Korea right now? Mr. Kitagawa will provide analysis and explanations.

Moon Jae-in Administration VS Yoon Seok-yeol Prosecution

—What is Happening in South Korea Now?—

From the Resume of the Day

Space Tanpopo, March 30, 2021

Lecturer: Hirokazu Kitagawa (Editor of “Japan-Korea Analysis”)

※The following contains personal supplements to the lecture material, so responsibility lies with Soka.

※I recommend watching Mr. Kitagawa’s lecture video above while reviewing this for better understanding.

Introduction

Methodology of “Japan-Korea Analysis”/“Editorial Side Notes” (Asahi, February 14)

→ Points out that “the Moon administration is not liberal.”

Japanese media tend to judge solely based on whether someone is “anti-North Korea” or “pro-Japan (government).” If not, everything is considered negative. This oversimplification completely ignores the complex realities of a divided nation, the history of friendship marred by past invasions, and the nuanced circumstances that cannot be reduced to binaries.

Ⅰ. What Deep-Rooted Corruption Did the Moon Administration Aim to Eliminate?—Democratization as the Aspiration of the Candlelight Revolution

1. Breaking Political and Economic Collusion and Democratizing the Economy

- The Korean people entrusted the Moon Jae-in administration with the task of eliminating deep-rooted corruption born under the Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye administrations through the Candlelight Revolution.

- There was frequent political and economic collusion, such as bribery involving Park Geun-hye and Lee Jae-yong, the Vice Chairman of Samsung Electronics.

- The negative impact of chaebol (conglomerate) economic dominance includes widening wealth gaps, increased poverty among young people, and families without wealth being unable to afford education costs. → Many young people cannot secure jobs at conglomerates, leading to a “Three No Generation”.

・The elimination of deep-rooted corruption was the wish of the Candlelight Revolution’s people, and Moon Jae-in was the candidate who fully embraced and promised to fulfill it. → Political democratization, eradication of monetary dominance, and economic democratization.

・A society where young people cannot afford to have children (birthrate at 0.8, a severe demographic decline).

・The Moon administration severed political and economic collusion, but the chaebol structure itself remains untouched, meaning “economic democratization” has not been achieved. Samsung alone accounts for 20% of South Korea’s GDP, wielding immense power.

Three No Generation (Three Give-Ups): Refers to a generation of young people who have given up on love, marriage, and childbirth. This is viewed as a result of the growing number of working poor in South Korea, who are underpaid and face precarious employment. Terms like “Five Give-Ups Generation” (giving up employment and home ownership) and “Seven Give-Ups Generation” (additionally giving up human relationships and dreams) have also emerged (Wikipedia).

2. Political Democratization—Prosecutorial Reform as Moon’s Top Policy Promise

※ President Moon’s top promise in the realm of “political democratization” was prosecutorial reform.

(1) Suppression of Democratization and Labor Movements in South Korea

- KCIA → Agency for National Security Planning → National Intelligence Service

- The expansion of prosecutorial power is linked to Japan’s colonial rule over Korea.

・In addition to prosecutorial powers (judiciary), they also hold ordinary investigative powers (policing), unlike most foreign countries.

・Using the “National Security Law,” they wield immense power to suppress democratization and labor movements.

→ During the colonial period, Japanese police had prosecutorial powers, enabling them to suppress dissent freely, leading to bloated police authority. After independence, measures were introduced to weaken police power to restore balance.

(2) The Conflict Between the Moon Administration and the Prosecution

Details of Prosecutorial Reform: Abolishing prosecutorial policing powers and limiting them to prosecutorial functions, aligning with international norms. A specialized and politically neutral investigative body (the Corruption Investigation Office for High-Ranking Officials) was established to handle crimes by those in power. This shifted the prosecution from an institution of arbitrary political repression to a standard administrative body like in other countries.

- August 9, 2019: President Moon announces a cabinet reshuffle, appointing Cho Kuk, Senior Presidential Secretary for Civil Affairs, as Justice Minister. → Cho’s strong focus on prosecutorial reform sparked intense resistance from the prosecution.

- August 26: Ruling and opposition parties announce a personnel hearing for Cho Kuk in early September.

- August 27: The Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office, just before the hearing, launches a forced investigation into Korea University and other related sites, alleging Cho’s daughter gained university admission and scholarships through fraudulent means. Subsequently, conservative media outlets leak allegations, including that Cho’s wife forged a university president’s award certificate.

- Japanese media, especially TV talk shows, attack the Moon administration using conservative newspaper articles as their source.

→ Some only introduced Sankei Shimbun editorials, claiming them as representative of Japanese opinions. - September 6: At the National Assembly hearing, Cho denies the allegations and claims innocence.

The prosecution indicts Cho’s wife for document forgery without prior questioning, prompting criticism from Prime Minister Lee Nak-yon.

This political indictment coincided with the hearing, bypassing standard procedures. - September 9: Cho formally assumes office as Justice Minister.

The prosecution requests an arrest warrant for a private fund representative, alleging Cho’s wife made opaque investments. → The court rejects the request. - September 16: Hwang Kyo-ahn, leader of the opposition Liberty Korea Party, shaves his head in front of the National Assembly in protest, demanding Cho’s resignation. Conservative opposition supports the prosecution.

- September 17: The Justice Ministry launches the “Prosecutorial Reform Support Team” to establish a new investigative body for high-ranking officials, laying the groundwork for the Corruption Investigation Office.

- September 23: As retaliation, the Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office raids the Justice Minister’s residence without specifying charges.

- September 25: The prosecution questions Cho’s son, alleging he used a falsified internship certificate for graduate school admission. Conservative media amplifies these allegations in support of the prosecution.

- September 28: The “National Solidarity for Judicial Reform and Elimination of Deep-Rooted Corruption” organizes a candlelight rally with 2 million participants outside the Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office, signaling public support for reform.

- October 14: Justice Minister Cho presents a comprehensive prosecutorial reform plan but announces his resignation, stating, “I cannot burden the government further with my family’s issues.” (End of the first chapter)

Japanese media did not report on the strong public support for prosecutorial reform.

3. Why Did the Conflict Occur?

- Both South Korean conservative media and Japanese press reported that the prosecution was uncovering corruption in the Moon administration, and the Moon administration pressured the prosecution to stop.

- The truth is exactly the opposite: As evidenced by the sequence of events above, prosecutorial reform preceded the conflict. The prosecution resisted reform and exerted pressure on the Moon administration to halt it.

4. Act Two of the Conflict—The Clash Between Justice Minister Choo Mi-ae and Prosecutor General Yoon Seok-yeol

- December 30, 2019: The South Korean National Assembly passed and enacted the bill to establish the Corruption Investigation Office for High-Ranking Officials (CIO).

- December 31: The Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office indicted former Justice Minister Cho Kuk on 12 charges related to family misconduct allegations.

→ Why did they continue pursuing Cho even after his resignation?

It was a warning to his successor: “If you pursue prosecutorial reform, we will come after you too.”

The South Korean prosecution often conducts forced investigations on former presidents (or their relatives if direct access is not possible) after they leave office to send a clear message to the new president: “Don’t challenge our power.” Known as the “fourth power” comparable to the three branches of government, they have suppressed labor and civil movements, distorting South Korea’s democracy as one of its most significant political impediments.

- January 2, 2020: President Moon appoints Representative Choo Mi-ae as Justice Minister, succeeding Cho Kuk.

- January 8: Justice Minister Choo announces a reshuffle of 32 senior prosecutors.

- January 23: Justice Minister Choo announces personnel changes for 759 prosecutors.

- January 31: Prosecutors raise allegations about Justice Minister Choo’s son’s military service. Conservative media reports heavily on this.

→ Claims of “improper extension of military leave” were later proven baseless, as it was due to a foot surgery. Despite efforts, the prosecution failed to turn this into a substantial case. - April 15: South Korean general election: Moon administration achieves a landslide victory, becoming the largest ruling party since democratization.

・Ruling “Democratic Party of Korea”: 128 → 180 seats (out of 300 total seats)

・Opposition “United Future Party”: 112 → 103 seats

・Opposition “Justice Party”: 6 → 6 seats

>[Reference] Detailed Analysis of South Korea’s General Election (Japan-Korea Network, Kamome) - November 24: Justice Minister Choo requests disciplinary action against Prosecutor General Yoon Seok-yeol and orders his suspension.

- Early December: Prosecutor General Yoon is reinstated, and the disciplinary action is dismissed.

- December 10: The National Assembly passes and enacts the amendment bill for establishing the Corruption Investigation Office for High-Ranking Officials (CIO).

- December 15: President Moon declares, “Democratic reforms have been achieved.”

- December 16: Justice Minister Choo announces her resignation. Park Beom-gye is appointed as her successor.

→ Japanese media portrayed this as a “defeat for the Moon administration,” but the reality was the opposite. - December 30: Kim Hyun-sung, a constitutional researcher, is appointed as the first head of the CIO.

→ Previously, no oversight body existed to monitor prosecutorial misconduct, making the prosecution an all-powerful and untouchable entity. Now, the prosecution is within the jurisdiction of the CIO.

5. Developments in 2021

- January 2021: The Corruption Investigation Office (CIO) was officially launched, and the law transferring investigative authority from the prosecution to the police was implemented.

→ To prevent excessive centralization of police power, law enforcement was divided into local (autonomous) and national (central) police.

Democratic reforms were successfully achieved, marking the Moon administration’s victory over prosecutorial power. - February: Democratic Party lawmakers propose a law to establish the “Serious Crimes Investigation Office,” transferring investigative authority for six major crimes (corruption, economic crimes, public office crimes, election crimes, defense industry crimes, and major disasters) to a new office within the police. Reports suggest the law could be enacted as early as March.

- March 4: Prosecutor General Yoon Seok-yeol submits his resignation to the Ministry of Justice, despite not completing his term.

→ His statement, “My mission in the prosecution ends here,” was interpreted as both a concession of defeat and a hint at running for president with a conservative party.

Ⅱ. Remaining External Deep-Rooted Corruption

1. The U.S. Obstructs Peace Efforts Through Inter-Korean Exchanges

- President Moon, reflecting the wishes of the South Korean people, held a summit meeting with General Secretary Kim Jong-un.

- The Trump administration forcibly established the “U.S.-ROK Working Group.”

The Biden administration has maintained this group while continuing to conduct joint U.S.-ROK military exercises.

2. Colonial Rule as a Significant Deep-Rooted Issue to Be Addressed

(1) Issues with the Japan-South Korea “Comfort Women” Agreement

(2) The Suga administration’s claim of “sovereign immunity” in response to court rulings

(3) South Korea’s Supreme Court ruling in favor of former forced laborers

(4) Responsibilities for Prime Minister Suga: “Engage in diplomacy with South Korea,” “Work towards resolving historical issues,” and “Clarify historical understanding.”

The End

For reference: South Korean Movie “The King”

The South Korean blockbuster “The King” is an entertaining film set against the backdrop of the prosecution system. While it includes many comedic elements and does not carry an overtly heavy political tone, it offers valuable insight into the concept of “prosecutorial power,” which might be less familiar to audiences in Japan. It also sheds light on how the world of prosecutors is perceived in South Korea.

To fully enjoy the movie, it helps to understand the context: South Korea’s prosecution holds dual powers of investigation and indictment, making it a uniquely powerful institution.

While the film is not inherently political, it does touch on a significant episode from South Korean history: President Roh Moo-hyun, who once attempted to reform the prosecution, was thoroughly crushed by the prosecution, which allied itself with the conservative media and opposition parties. Even after his presidency, the prosecution orchestrated large-scale scandals around his associates as a warning to subsequent administrations, ultimately driving him to take his own life.

Until the Candlelight Revolution, “prosecution reform” was an untouchable subject for all South Korean politicians. When the Moon Jae-in administration took on this challenge, it unfolded much as predicted, but it persisted until the end. The key to this success lay in lessons from the Roh Moo-hyun administration: During his tenure, many of his supporters quickly distanced themselves from him, avoiding involvement in the scandals. This allowed the prosecutorial power to remain unchecked. Moon Jae-in’s administration benefitted from a collective resolve within the human rights community to stay united in their support for the government and prosecution reform, ensuring no divisions emerged.This steadfast unity among human rights advocates became the driving force behind the eventual success of the reform.

【Spoiler Alert】Synopsis of “The King”

A Hotheaded Youth Aspires to Become a Prosecutor!

Park Tae-soo (played by Jo In-sung), a young man from the rural port town of Mokpo, grows up in a turbulent environment with his father, a petty criminal who makes a living by stealing and selling items like color TVs and household appliances. During his rebellious high school years, Tae-soo witnesses a prosecutor controlling his father with absolute authority.

Awestruck by the prosecutor’s power to dictate sentences and lives, Tae-soo becomes determined to pursue the same career. Despite his poor academic record, he throws himself into his studies. His perseverance pays off as he transforms from a struggling student into a top performer, eventually earning admission to Seoul National University, graduating, and passing the bar exam. Tae-soo’s rise catapults his family out of poverty and into wealth, and he marries the beautiful and sophisticated Sang-hee (played by Kim Ah-joong).

However, Tae-soo’s new job as a prosecutor is far less glamorous than he imagined. Tasked with handling over 30 minor cases a day, none of which make the front page, he begins to feel disillusioned. He comes to a stark realization: only 1% of prosecutors handle the high-profile cases that dominate the news, while the other 99%—himself included—are relegated to less significant cases.

Meeting Chief Prosecutor Han Kang-sik

One day, Tae-soo is assigned a case involving a high school gym teacher accused of sexually assaulting a female student. Unlike the usual suspects who cower before prosecutors, this teacher remains unusually confident. Tae-soo later discovers that the teacher used his connections—his father, a former member of the National Assembly—to cover up the incident. Furious, Tae-soo becomes determined to push for a prison sentence.

Amid this turmoil, Tae-soo receives a sudden invitation from Yang Dong-chul (played by Bae Sung-woo), a senior prosecutor working in the “Strategic Division” of the Seoul Central District Prosecutors’ Office. Dong-chul introduces him to the division’s secretive practices, including a storeroom full of unresolved cases involving powerful figures, which the division strategically “ages” for leverage. Dong-chul offers Tae-soo a deal: drop the case against the gym teacher in exchange for a recommendation to the division’s chief, Han Kang-sik (played by Jung Woo-sung). It becomes clear that the gym teacher’s father had already secured Han Kang-sik’s influence behind the scenes.

Han Kang-sik is a formidable figure, feared for his ability to bring down business tycoons, political elites, and celebrities with targeted prosecutions. People believe that “once Chief Han has you in his sights, it’s over.” At the same time, he epitomizes success, hosting extravagant penthouse parties attended by the upper echelons of society. When Tae-soo attends one of these parties, he initially intends to confront Han with his ideals of justice. However, overwhelmed by Han’s charisma and dominance, Tae-soo abandons his ideals in favor of ambition.

“Align yourself with power! Ditch your pride!”

Impressed by Han Kang-sik, Tae-soo becomes consumed with the desire to join the elite 1% of prosecutors, driven by ambition to rise within the system at any cost.

An Unexpected Reunion with a Friend

On his way home from Han Kang-sik’s party, Tae-soo finds himself unable to suppress his anger toward the gym teacher present at the event. The situation almost escalates into a confrontation when a familiar face intervenes—Tae-soo’s childhood friend, Doo-il (played by Ryu Jun-yeol). Now a member of Mokpo’s violent gang known as the “Stray Dogs,” Doo-il steps in, vowing to handle any dirty work needed to help Tae-soo rise to the top of the prosecution world. Despite their divergent paths in life, their friendship remains unshaken, and Doo-il is the one person Tae-soo can truly confide in.

Once Tae-soo earns Han Kang-sik’s favor and secures a position in the Strategic Division, his career takes off. Tae-soo begins using his newfound power to secure Doo-il’s release from prison and improve the status of his news anchor wife. However, in the political world, a change in administration is a perilous time for prosecutors. The members of the Strategic Division resort to any means necessary—no matter how unethical—to protect themselves and secure promotions, including manipulating public opinion by leaking sensational news, such as a pure-hearted idol’s drug scandal.

“In politics, you retaliate when attacked,” and “You bury one scoop with another.” These are the norms of their world. Han Kang-sik, Dong-chul, Tae-soo, and Doo-il indulge in extravagance, renting out restricted beaches for wild parties. Tae-soo begins to feel like an untouchable, as if he were part of an unstoppable and ruthless criminal organization.

However, the tides shift when Ahn Hyeon (played by Kim So-jin), a female prosecutor from the Inspection Division, begins investigating Han Kang-sik and his allies. Her actions threaten to unravel the corrupt empire Tae-soo has aligned himself with, setting the stage for a dramatic showdown.

Dark Clouds Gather Over Tae-soo’s Life

The first target in Ahn Hyeon’s attempt to bring down Han Kang-sik was none other than Tae-soo. Tae-soo’s life was riddled with vulnerabilities: his family’s issues, rumors of an affair with a celebrity defendant, and his unbreakable ties to his gangster friend Doo-il. These whispers of scandal reached Han Kang-sik’s ears, further damaging Tae-soo’s standing. Matters worsened when Tae-soo’s wife discovered his affair, leading her to demand a divorce. Meanwhile, Doo-il had left the “Stray Dogs” gang and was rapidly expanding his influence in Seoul’s Gangnam district.

As another presidential election approached, Roh Moo-hyun emerged as the frontrunner. This development terrified Han Kang-sik and his allies, as Roh, a former lawyer, had openly advocated for prosecution reform—a direct threat to their power. In preparation, Han provided damaging information to the opposition to undermine the ruling party and even sought the aid of a shaman to pray for Roh’s defeat.But Roh Moo-hyun won the election.

As predicted, Han’s position began to erode. To make matters worse, newspapers exposed a scandal involving Doo-il, revealing his ties to Tae-soo. The revelation cost Han the Chief Prosecutor role, sending him into a furious rage. In retaliation, he ordered Tae-soo to arrest Doo-il. Tae-soo faced a moral crisis, torn between his loyalty to Doo-il, who had always supported him, and his inability to defy Han’s command.

Adding to the chaos, President Roh Moo-hyun faced impeachment proceedings, allowing Han Kang-sik to regain influence within the prosecution. Han, now viewing Tae-soo as a liability, orchestrated his transfer to a remote district, effectively sidelining him.

The Ending of “The King”

Tae-soo had been entrusted with the money Doo-il had painstakingly saved during his imprisonment. However, instead of returning it to the “Stray Dogs” gang, he kept it for himself, indulging in a life of decadence in a secluded countryside villa. When Ahn Hyeon came to question him for information, Tae-soo feigned ignorance to avoid trouble. Upon his release as a model prisoner, Doo-il discovered the betrayal and, shocked and furious, headed straight to confront Tae-soo.

One night, Han Kang-sik and Yang Dong-chul paid an unexpected visit to Tae-soo, suggesting a night out together. Overcome with nostalgia and excitement, Tae-soo joined them in their car. On the way, however, Doo-il’s car rammed into theirs. Though Tae-soo, Kang-sik, and Dong-chul survived, they were severely injured in the crash.

Doo-il had uncovered Kang-sik’s connection to the “Stray Dogs” boss (played by Kim Ui-seong). Determined to protect Tae-soo, who had once vowed to support him, Doo-il donned a tailored suit and confronted the gang boss. Tragically, he was overpowered and met a gruesome end, fed to dogs in the gang’s most brutal execution method. As his life ebbed away, Doo-il saw the boss calmly drinking coffee, with Kang-sik standing by his side.

Soon after, Tae-soo’s father was unexpectedly arrested. The authorities offered to release him on the condition that Tae-soo resigned from the prosecution. To protect his father, Tae-soo agreed, only to have his family home and possessions seized. Drowning in alcohol and despair, Tae-soo hit rock bottom, realizing that Kang-sik and Dong-chul had stripped him of everything. But then, Tae-soo resolved: “I can’t go on like this.” He stood up to fight back.

Following Doo-il’s example, Tae-soo tailored a suit, bought a new car, and set up a new office in Seoul. He reconciled with his estranged wife Sang-hee, apologizing and mending their relationship. This time, Tae-soo decided to enter politics. With the support of Sang-hee’s politically connected father and Ahn Hyeon, who was eager to bring down Kang-sik, Tae-soo exposed Kang-sik’s corruption and dethroned him from his position as the “king” of the prosecution.

The story concludes with Tae-soo running in a fiercely contested election in central Seoul, facing off against a leading presidential candidate. As the election results loom, Tae-soo utters the iconic line: “You are the king of this world.” Whether Tae-soo wins or loses remains left to the audience’s imagination.

Donations are made in Japanese yen. 300 yen is approximately 2 USD.

Donations are made in Japanese yen. 300 yen is approximately 2 USD.

Mr. Kitagawa’s lecture clearly conveys the significance of the reforms carried out by the Moon Jae-in administration, particularly focusing on prosecutorial reform from a progressive perspective. The reforms, supported by the power of the citizens that emerged during the Candlelight Revolution, undeniably played a critical role in advancing democracy in South Korea.

However, the Moon administration also had its limitations. Economic democratization and chaebol reforms remained insufficient, and responses to structural issues such as low birth rates and youth poverty were limited. Moreover, progress in inter-Korean relations fell short of the expectations set at the outset.

What deserves attention is that support for these reforms was not limited to progressives. Even some conservatives voiced the need to curb prosecutorial power. Prosecutorial reform went beyond the “progressive vs. conservative” divide, reflecting the broader demand of South Korean society for a fairer and more transparent judicial system.