Table of Contents for the Senki-ha Photo Collection

Nostalgic Archive Top Page

- 1 About the "Senki-ha Collection"

- 2 About the Immediate Operational Policy

- 3 What is the "Senki-ha"? ─ About the Communist League (Senki-ha) and the Battle Flag Communist League

- 4 1970: The Split of the Second Bund and the Formation of the "Senki-ha"

- 5 Memo: The Pronunciation of "Bund" as "Bunto" or "Bund"

- 6 Acknowledgments: Websites and Resources Referenced

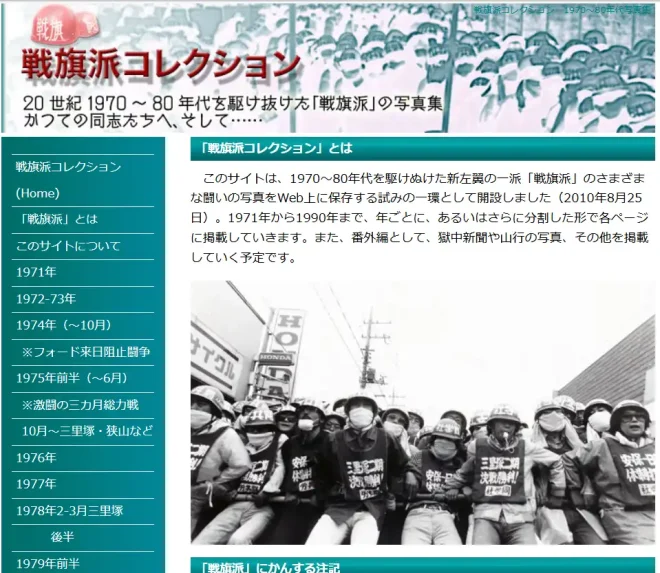

About the “Senki-ha Collection”

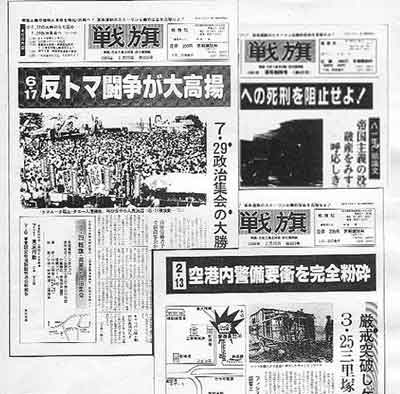

The “Senki-ha Collection” was a website launched in August 2010 as part of an effort to preserve photos from the various struggles of the New Left faction “Senki-ha,” which was active during the 1970s and 80s. By the spring of 2021, the site became inaccessible (perhaps removed?) and is no longer available for viewing.

Soka, the administrator of this site, “Bund,” was personally acquainted with the administrators of the “Senki-ha Collection” and had verbally received permission to reproduce their photos. Especially after confirming the site’s disappearance, I felt compelled to preserve and extend its content as a “Bund version.” That is the context behind its publication on this site.

The commentary in this article and other explanations are significantly expanded and restructured from multiple pages of the former “Senki-ha Collection” to make them relatively easier to understand for readers unfamiliar with the Leftist experience. The responsibility for these changes lies with me, Soka. (Contact me here for comments or information.)

The administrators of the “Senki-ha Collection” and “Bund” were once members of Senki-ha but have since left the faction. We have no connection with its successor organizations or activities. Descriptions on this site reflect personal experiences and are not necessarily aligned with the views of the former Senki-ha. Furthermore, the accuracy of the content is not guaranteed; those wishing to verify historical facts are encouraged to treat this as one among many personal testimonies. Feel free to reproduce or quote the content, but please acknowledge that any consequences arising from such actions are the responsibility of the party using it.

About the Immediate Operational Policy

The background of this site’s creation has been explained above. Some may wonder, “What about critical reflection?” However, for now, I will limit the discussion to our immediate operational policy.

The former administrators of the “Senki-ha Collection” held a set of photos capturing moments from the 20-year history of Senki-ha (later, an additional collection of film reels was added). Some were organized chronologically, while others remained in bulk. Many of the organized photos overlapped with the contents of the photo book “The Northwestern Wind Strengthens the Party” (published in 1984 by Senki Publishing, parts 1 and 2).

The “Senki-ha Collection” primarily featured these organized photos, displayed chronologically by year from 1971 to 1990. This site will initially reproduce and preserve the contents of the “Senki-ha Collection” up to 1990 (or as appropriate), after which additional photos from private collections, online sources, and printed materials scattered across various places will be included. (For online sources, see “Acknowledged Sites” below.)

Additionally, the site plans to feature bonus content from the former “Senki-ha Collection,” such as prison newspapers, photos from mountain expeditions, and others. Unfortunately, only fragments of the mountain expedition photos have been preserved on this site (“Bund”).

Mountain expeditions, in particular, represent a significant part of the memories of former Senki-ha members—perhaps half of them (?). If any former administrators of the “Senki-ha Collection” or anyone in possession of mountain photos, private collections, or back issues of “Senki” or “Tōrō” wishes to make them publicly available in a similar format to this site, we will respect your privacy. Please feel free to contact us.

What is the “Senki-ha”? ─ About the Communist League (Senki-ha) and the Battle Flag Communist League

Notes on the “Senki-ha”

The term “Senki-ha” as used here refers to a New Left organization that operated under the names Communist League (Senki-ha) and Battle Flag Communist League from the 1970s to the 1990s. It was also referred to derogatorily as the Hyūga Faction or Ara Faction. Most of those involved are now in their 40s to mid-70s, living quietly with varied memories.

Historically, there have been other groups called “Senki-ha,” such as the faction associated with proletarian literature in the 1920s, known for Takiji Kobayashi’s “The Crab Cannery Ship”, and the faction that emerged during the split of the First Bund in the 1960 Anpo Struggle. However, these are unrelated to the “Senki-ha” discussed here.

The origins of Senki-ha trace back to the Communist League (Second Bund), rebuilt in 1966, and the National Committee of the Socialist Student League. It was formed during the split of the Bund around the time of the 1970 Anpo and Okinawa struggles and took the name Communist League (Senki-ha) as one of its factions. It was also referred to by others as the “Theoretical Front Faction,” named after the journal of the National Committee of the Socialist Student League.

As described above, this photo collection is a narrative of events from the perspective (subjective) of the Senki (Hyūga) Faction. We believe there is no reason for criticism in this regard. This is not an attempt at comprehensive academic research. If anyone from other factions finds our descriptions unsatisfactory, we encourage them to create their own “XX Faction Collection” from their perspective. It would be beneficial for third parties to compare and explore multiple perspectives.

The “Senki-ha” Naming Issue

As mentioned above, the name “Senki-ha” is inherently ambiguous, making it difficult to pinpoint the exact group it refers to. This confusion stems partly from the fact that “Senki” was the official central organ paper of the Bund since its establishment in 1958. As a result, the term “Senki-ha” became a provisional label for factions controlling the publication rights of this central paper, often referred to as the “Central Leadership Faction” or “Secretariat Faction.”

For example, during the splits in the Second Bund around 1970, the faction that remained within the party after the “Red Army Faction” broke away was called “Senki-ha.” Similarly, during the splits involving the Han-ki (Rebellion) and Jōkyō (Situation) factions, the remaining core Bund was also referred to as “Senki-ha.” The 1973 split of Senki-ha further complicated matters, as multiple factions with the same name coexisted.

To distinguish between the two factions using the same name, the group referred to here as Senki-ha was nicknamed the “Hyūga Faction” after its leader’s pen name. The other faction, known as the “Nishida Faction” (currently the Communist League [Unified Committee]), was one of several groups that emerged. Other factions included the “Proletarian Senki Faction” and the “Internationalist Faction.” In 1980, to avoid confusion, the group changed its name to Battle Flag Communist League.

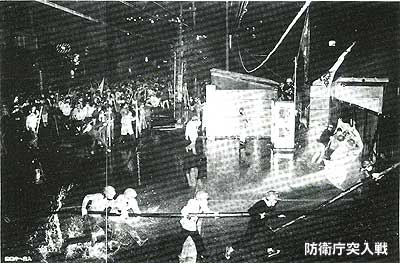

During this period, the faction engaged in significant struggles, including the Sayama Discrimination Trial Protests, the rebuilding of the Sanrizuka Struggle Group, and the March 26, 1978, Airport Control Tower Occupation, in collaboration with the Fourth International and other “Red Helmet Factions.” After adopting the name “Battle Flag Communist League” in the 1980s, the group also carried out guerrilla and partisan combat activities, such as the anti-monarchy struggle.

Incidentally, during the Sanrizuka Struggle, local farmers distinguished the factions by the locations of their solidarity huts. The faction discussed here (Battle Flag Communist League) was called the “Yokobori Senki”, while the Nishida Senki faction was called the “Iwayama Senki.”

In the 1990s, Senki-ha abandoned its factional name and became known as the “Communist League.” It then shifted to being the “Bund” without a goal of communist revolution, and eventually transformed into “Actio, a General Incorporated Association for Eco & Peace.” Thus, Senki-ha as a New Left organization dissolved and ceased to exist.

With that said, we will set aside the naming issue here. In the following sections, we will focus on key milestones between 1970 and 1990, annotating aspects of Senki-ha’s history that cannot be captured through photographs (names are without honorifics, primarily pen names, and faction names include a mix of self-designations and colloquial terms).

1970: The Split of the Second Bund and the Formation of the “Senki-ha”

a. 1969: The Second Bund After the Red Army Split on July 6

The Second Bund lacked a strong central faction from the start. In 1969, when Ken Ichikō (Takaya Shiomi) and his group, who strongly advocated armed uprising, forcibly split off as the “Red Army Faction”, the party fell into chaos. Independent actions by intra-party groups, the autonomy of local organizations, and complex alliances became more pronounced.

Even the Japanese Communist Party, as well as surviving factions like the Revolutionary Communist League-Chukaku-ha, Kakumaru-ha, and Shaseido Liberation Faction after the 1970 Anpo Struggles, maintained relatively strong central leadership. In contrast, factions without such leadership, like ML Factions or Structural Reformist Groups, often faced division and dissolution.

Looking at the student movement, in the Tokyo metropolitan area, the leadership of Gakutai (Student Committee) and the Socialist Student League (Shagakudo) was imprisoned during events such as the January 1969 Yasuda Auditorium battle at Tokyo University and the Anpo-Okinawa Struggles post-April 28. With leadership absent, about half of the remaining students joined the Red Army Faction, plunging student and high school organizations into complete disarray.

Amid this chaos, the Han-ki Faction from Chuo University Bund unexpectedly found itself in a dominant position in the Tokyo metropolitan area, largely unshaken by the turmoil. The Jōkyō Faction from Meiji University’s Independent Socialist Student League also revived as most leftist students from Meiji University had departed, enabling its resurgence.

In the Kansai region, students who did not join the Red Army Faction, particularly those who had moved to Tokyo, began to drift toward becoming “Red Helmet Non-Sects” or returned to the Kansai Bund, a regional independent force from before the formation of the Second Bund centered on labor organizations like Osaka Chuden.

Despite the efforts of Secretary General Sasaki and other remaining Gakutai members in Tokyo, the Autumn 1969 Anpo Struggle ended in disappointment. With key figures like Toshio Fujimoto (Chairman of the Anti-Imperialist Zengakuren) leaving the movement upon release from prison, the Bund entered 1970 in dire straits.

b. The Second Bund in Early 1970

Aside from the central organ paper “Senki”, numerous local, prefectural, and district committee publications were independently (and sometimes arbitrarily) issued. These publications became focal points for the organization of various intra-party factions. Although it may be a bit tedious, here is a rough summary, including their fate after the dissolution of the Bund.

■“Senki” and “Communism”

Published by: The Communist League (inheriting the name of the First Bund’s organ paper). Around 1969-70, the editors and publishers of “Senki” were Kazuo Sasaki and Susumu Noda. The central Secretariat and Editorial Bureau coordinated the various factions. The office (Senki-sha) located in the Takizawa Building’s basement (2-7-6 Misakicho, Chiyoda-ku, near Suidobashi Station on the Sobu Line) became a target for disputes among factions.

■ “Theoretical Front”

Published by: Theoretical journal of the Socialist Student League, later the Communist Youth League. Written by key figures who would later form the Senki-ha, including Susumu Noda (editor-in-chief of “Senki”), Kakeru Hyūga (chairman of the Socialist Student League), Hiroshi Ise (Student Committee), Tetsu Shiroyama, Yasushi Muranaka, Fumito Akai, and Teru Nishida. The term “Theoretical Front Faction” was derived from the name of this journal.

→ From 1980, it became the theoretical journal of the Battle Flag Communist League.

■ “Han-ki” (“Rebellion Flag”)

Published by: Tokyo Mitama District Committee (first issued in November 1968). Figures such as Osamu Mikami and Akira Kōzu (Chuo University Bund). → The Han-ki Faction was established in June 1970. The faction had a strong base among students, including at Aoyama Gakuin University and other institutions in the Tokyo metropolitan area. On June 11, during a Communist League political rally at Toshima Public Hall in Ikebukuro, Tokyo, the Han-ki and Jōkyō coalition attacked the Senki-ha coalition, cementing the split. → In 1975, Osamu Mikami withdrew, and the faction disbanded by the end of 1976.

A “Former Han-ki Mutual Aid Society,” believed to have been established to support defendants of the September 16 Higashi-Funo Crossroads Struggle, continues to exist under Akira Kōzu’s leadership.

■ “Iron Front”

Published by: Tokyo Southern District Committee. Key figures included Tokujirō Saragi, chairman of the Eighth Communist League Congress. This faction, including Southern District members, Senshu University Socialist Student League, and medical students, became the “Uprising War Faction” on December 18, 1970, later known as the “Iron Front Faction.”

→ Split into the Uprising Faction (nicknamed the “Saragi Faction,” publishing “Uprising”) and the Uprising Left (led by Akio Sato, later the editorial committee of “Proletarian Communication” of the Communist League). In 1998, Tokujirō Saragi withdrew, and the publication was renamed “Red Star”.

→ In March 2009, Makito and Takashi Akai (Communist League Uprising Faction) formed the “Communist Association” (publishing “Red Proletarian”, abbreviated as “Red Pro”) with figures like Bunji Hatakenaka (Jōkyō Faction) and Bontaro Asahi (Kanagawa Left Faction). “Red Star” merged into “Red Pro” and ceased publication. → In January 2016, it was reissued under the title “The Red Stars”. The association has since disbanded.

Note 1) The Uprising War Faction refers to a self-designated coalition active during the April 28, 1971 Okinawa Day.

This coalition included the 12.18 United Bund (composed of the Kanagawa Left Faction, Kansai Regional Committee Faction, and the Saragi Faction), the Communist League Red Army Faction, Keihin Anpo Joint Struggle, Red Helmet Non-Sects from Doshisha University’s All-Campus Struggle and Kyoto University’s C Front, among others.

It was not necessarily the name of a distinct faction. [The Saragi Faction reportedly did not participate in the meeting but only joined the demonstration.] At Hibiya Park’s Nishi-Saikō Gate, they clashed with the Senki-ha (→ see 1971), but organizationally, the clash involved only the 12.18 United Bund.

Within the Senki-ha at the time, this coalition was disparagingly referred to as the “Opportunistic Right Wing.”

■ “Left Faction”

Published by: Kanagawa Prefectural Committee (first issued in January 1970). Led by Bontarō Asahi (member of the Kansai Delegation to Tokyo and a member of the Political Bureau of the 7th Congress). → On December 18, 1970, it became part of the “Uprising War Faction” and later the (Kanagawa) “Left Faction.”

→ Subsequently evolved into the Communist League Proletarian Communication Editorial Committee (also known as the “Toshima Group,” reportedly a merger of the Uprising Left and a minority from the Red Report Faction). → In 2009, it joined the aforementioned “Communist Association.”

■ “Beacon Fire” (“Noroshi”)

Published by: Kansai Regional Committee (reissued in August 1970) → In December 1970, became the “Uprising War Faction” and later the “Beacon Fire Faction.” Split into the Communist League National Committee (Beacon Fire Faction) and the “Red Report Faction” led by Hitoshi Ebara, known as the Communist League (RG).

→ In 2004, the National Committee faction merged with the Senki Nishida Faction to form the Communist League (Unified Committee), with “Senki” as its publication.

Note 2) RG is an abbreviation of the German term Rote Gewalt (pronunciation: “Rote Gewalt,” literally “Red Power” or “Red Violence,” loosely translated as “Communist Assault Corps”). It is pronounced “Erugē” in Japanese. Originally conceived by Ken Ichikō (Takaya Shiomi, member of the Kansai Delegation to Tokyo and Political Bureau member of the 7th Congress, later the leader of the Red Army Faction). During the April 28, 1969 Okinawa Struggle, it was used as the name for the Socialist Student League and other squads that seized the MD (Tokyo Medical and Dental University) the night before, broke through police barricades, and marched from Akihabara Station toward the central district of Tokyo. Subsequently, Ken Ichikō and others moved toward the establishment of a more militarized “Red Army.” Meanwhile, following the split of the Red Army Faction, RG was organized within various Bund factions (excluding the Han-ki and Jōkyō factions) as a small elite force in preparation for the 1969 Autumn Anpo and Okinawa Struggles. Later, Hitoshi Ebara and others adopted the name RG for their faction during their split from the Kansai-based Beacon Fire Faction.

■ “Jōkyō” (“Situation”)

The Jōkyō Faction (Meiji University Independent Socialist Student League → Chairman of the 6th Congress, Reiji Matsumoto; Student Committee, Susumu Koga) split from the Bund in June 1970 and began publishing the journal “Rote” (published by the Preparatory Committee for the Reconstruction of the Communist League).

→ Later, Reiji Matsumoto published “From Afar.” Susumu Koga co-founded the second series of “Jōkyō” with Wataru Hiromatsu in 1990.

The Jōkyō Faction evolved through several iterations, including the Guerrilla Faction, the Flag of Revolution Faction, and the Red Flag Faction. In 2009, a faction of its lineage, the Metropolitan Area Committee, formed the above-mentioned “Communist Association.”

c. The Formation of the “Senki-ha”

In addition to the above, many “organ papers” were produced on B4-sized straw paper, printed with mimeograph machines and stapled together. Among these, the one that became the focal point for the eventual formation of the Senki-ha was:

■“Red Texas”

Published by: Tokyo Western District Anti-Imperialist Front. This was issued by the “Yōuntei Fraction”, which united parts of the student and high school organizations in the Tokyo metropolitan area and groups involved in the Tokyo University Struggle who had been released on bail after the Autumn 1969 “Anpo-Okinawa Struggles.” Major articles from this publication were later compiled in “Theoretical Front.”

This initiative also connected with regional organizations in Kyushu, Hokkaido, and Aichi, which maintained their distance from central and Kansai-based groups as described in the previous section. Additionally, some non-affiliated and non-sectarian students seeking a new direction after the All-Campus Joint Struggle joined in. Susumu Noda, editor and publisher of the central organ paper “Senki,” also participated.

Thus, a trend emerged demanding a transformation from the somewhat free but irresponsible “coalition party of various factions” into a “single centralized party” accountable to its local and grassroots bases. This trend quickly gained momentum and expanded its influence on the party’s central leadership, using the newly established party organ, the “Aoyama Organizational Committee.”

Eventually, as described earlier, after the Han-ki and Jōkyō factions split in June 1970, the remaining Bund core (referred to by others as the “Senki-ha”) experienced another division. On 12.18, the three factions aligned with the Uprising War Faction (Kansai Regional Committee Faction, Iron Front Faction, and the Kanagawa “Left” Faction) forcibly held an independent “Communist League Political Rally” under the banner of the “12.18 United Bund.” They jointly published their own version of “Senki,” declared a break from the central Senki Faction, and finalized their split.

On April 28, 1971, at Hibiya Park, the central Senki Faction sought to make a mass appearance at an Okinawa rally and engaged in a battle with the anti-Senki coalition, achieving a decisive victory. In the aftermath of this defeat, the December 18 United Bund fell into disarray and disbanded due to internal conflicts. Their version of “Senki” ceased publication (a total of 14 issues, numbers 250 to 264, which had coexisted alongside the central faction’s “Senki”). Each faction within the coalition fragmented, effectively dissolving the United Bund.

Subsequently, the Senki-ha declared a shift toward “the sublation of factional struggles and a focus on anti-power struggles.” Acknowledging that they themselves were one faction of the Bund, they adopted the name “Communist League (Senki-ha)” (see 1971). Although, as described in the previous section, alignments and separations among various factions continued, this marked a tentative resolution of the factional struggles within the Second Bund.

[Sōka’s Memo] In the factional struggles of the Communist League (Bund), each group claimed to be the legitimate central leadership, labeling others as anti-party elements or factions, and asserted their legitimacy to the masses. However, unlike the Japanese Communist Party or the Chukaku-ha, which had “strong central factions,” the Bund’s claims of legitimacy carried little weight for outsiders.

Nonetheless, once such claims were made, it became difficult to retract them later. Recognizing this reality was essential for ending factional struggles and returning to the primary focus on anti-power struggles. The decision to make this shift at the time has been regarded positively.

However, did this resolve all armed conflicts (gebalto) between factions or with other groups? The answer is no. It’s not so simple to say, “Let’s forget the past.”

While engaging in numerous anti-power struggles over the reversion of Okinawa, intermittent gebalto continued until early 1973. These involved the Red Army Faction and the ML Faction (the Maoist “Marxist-Leninist League” originating from the Bund, which split and dissolved after June 1970) in the first half of 1970, the Han-ki Faction from the latter half of 1970 to April 28, 1971, and the Uprising War Faction-related groups, the Jōkyō Faction, and non-sectarian groups (such as the Meiji University Press Association’s “MUP Joint Struggle”) after April 28. Notably, attacks on the MUP Joint Struggle and on “K,” a member of the “Association Supporting the Anti-Subversive Activities Law Trial Struggle,” were later self-criticized in ‘Senki.’ During this process, seeds of internal division began to sprout within the Senki-ha.

[Sōka’s Memo] Internal struggles between factions might be acceptable as long as they don’t cross the line—whether you win or lose, it’s self-inflicted. However, applying the same mindset to non-sectarian groups outside the party, like the MUP Joint Struggle, reflects poorly on the party’s morals and makes them no better than the Chukaku-ha. Self-criticism was inevitable. That said, the Chukaku-ha still hasn’t conducted any self-criticism for such actions, so in comparison, the Senki-ha was far better.

1973: The Split of the “Senki-ha”

In June 1973, during the 12th Central Committee Meeting held at a location in Kanagawa Prefecture, the Communist League (Senki-ha) effectively split (the split was finalized in October). This marked the collapse of the first phase of the Senki-ha, which had been built since the “Yōuntei Fraction” in early 1970, forcing a restart.

Explanations and justifications regarding the points of contention—such as the organizational structure, armed struggle, and policy disputes—and the circumstances leading to the split have been issued by various factions over time. However, the details are highly complex, and there is no way to fully account for every action of the Central Committee members at the time. Moreover, this is not the place to debate legitimacy. Thus, this section provides only an external overview.

Looking back chronologically, by the end of 1972, the Shibuya Group (later the Internationalist Faction) had been formed, and by March 1973, the “Adachi Shōkai” Group (comprising Nishida, Ōshita, and Shiroyama, which later split into the Nishida-Ōshita Faction and the Shiroyama Faction) emerged. “Adachi Shōkai” was a pseudonym for the office established by this group.

According to Nishida and his allies, the formation of these groups was a response to “the factional organizational management by the Hyūga Central Faction after the summer of 1972.” However, from Hyūga’s perspective, it was argued that “Nishida and his allies enclosed their respective districts and regions, forming factions by exploiting opposition to N’s bureaucratic management.”

It is worth noting that during this period, the organization operated under a structure consisting of a Congress, an (Expanded) Central Committee, and a (Standing) Central Committee, with local and regional committees under its jurisdiction. The (Expanded) Central Committees, labeled as “○th Session,” were composed of standing Central Committee members and representatives from local and regional branches. In the absence of a full Congress, this body served as the highest decision-making authority.

The following chart provides an overview of the respective factions’ influence (regions are categorized by majority affiliation; minorities are not listed unless the division is nearly equal. ★ indicates approximate strength. Faction names are based on the names of their respective publications with “Faction” appended).

One noteworthy aspect of the 1973 “Senki Faction Split” is that it did not escalate into internal violence (gebalto). While physical altercations such as fistfights were not entirely absent in subsequent years, neither side pursued the physical dismantling of the other as an objective.

The decision to steer away from the intensification and normalization of internal violence (gebalto) within the New Left, which had escalated around 1970, is actively praised within the Senki-ha’s history. This is seen as a concrete manifestation of self-criticism, such as for the attack on the MUP Joint Struggle, and as a reflection on the sectarianism and internal violence that had plagued the group.

That said, perhaps this framing is a bit too idealized. Friends lost, and comrades who shared both hardship and camaraderie, left the Senki-ha during and after the process of its split…

[Sōka’s Memo] They risked their lives, only to see their numbers reduced not just by half but to a third overnight. It must have been devastating… There were not only defectors but also reports of suicides.

Initially, the spirit of the Senki-ha activists, who had united under the Bund banner through struggles against the Vietnam War, the Anpo Treaty, Okinawa issues, and campus conflicts, was already exhausted and depleted by internal violence with other factions and non-sectarian groups, as well as by repeated factional struggles. By this point, they had neither the morale nor the resources to fight anything but state power. Many likely believed that they could continue their activism only if internal violence was absent, even if it could never fully heal their wounds.

On July 7, 1974, the Senki-ha declared a fresh start at a political rally under the banner of “Blood Debt and Reflection.” This marked the beginning of their second phase of development. From this point onward, free from the exhaustion of factional struggles and legitimacy disputes, they operated as a unified party. They engaged in struggles such as the Sayama Discrimination Trial Condemnation Struggle, anti-Emperor struggles, and the reconstruction of the Sanrizuka Struggle Front. They pursued these efforts by learning from and being supported by many people, rebuilding themselves from the ground up.

During this process, the Senki-ha also established a system for independently printing and publishing their organ paper, “Senki.” Initially using Japanese typewriters, they eventually introduced phototypesetting machines and printing presses. For a while, their publications took the form of B4 stapled booklets. It wasn’t until late 1980, after the renaming to “Senki-Communist League,” that the paper adopted a newspaper-style tabloid format (New Year issue, 1981).

It should be noted that “Senki-Communist League” translates to “Battle Flag Communist League (BFCL).” The organization adopted this abbreviation as its international designation.

A brief overview of the subsequent paths taken by the factions that split during the 1973 Senki Faction split:

- Hokkaido Communist League (= Shiroyama Faction)

I barely ever saw them in Tokyo, let alone in Kansai (though I might have spotted a few at Sanrizuka before the struggle split—my memory is hazy). However, I distinctly remember seeing a young woman in a red helmet (a student?) at Miyashita Park during the 1986 Anti-Emperor 60th Accession Anniversary Protest. She was weaving through the large Senki faction crowd, cheerfully greeting everyone with a “Hello!” and diligently handing out flyers on her own.

She had a round, youthful face (pardon my observation!) and looked so out of place. I thought, “She must have come all the way from Hokkaido, representing the Pro-Senki faction,” and found it oddly heartwarming. But then one of the leaders of the Socialist Student League stepped in, shouting, “What are you doing here?!” She replied, “What? Am I not allowed?” to which he retorted, “Of course not!” I watched her face stiffen from a distance and thought, “Oh no…” Perhaps factions typically coexist peacefully, but she probably didn’t know that! She came all the way from Hokkaido with her flyers—cut her some slack! (laughs). If I had kept one of those flyers, it would have been quite a rare find! - Internationalist Faction

I’ve never encountered them—on the internet or anywhere else (yes, I’m sure). Aside from their puzzling conclusion of becoming part of the Japan Communist Party (Action Faction), I know nothing about them. Originally, they were a tiny group of general members without a single Central Committee member. Even in documents criticizing other Senki factions, their name rarely appeared.

Generally, they are considered the smallest and furthest-left of the four factions (or rather, ultra-leftist). However, there is little evidence of notable activities. Judging by the publications of today’s Action Faction, I suspect they were less “ultra-leftist” and more doctrinaire (similar to the Fourth International’s Spartacist League). Their name, “Internationalist Faction,” also gives off that impression. Among the four factions, they were likely the group I would have clashed with the most. (laughs)

Excuse me, the Proletarian Senki faction had at least a group of four during the 1987 anti-Crown Prince visit protest at Haneda. I also heard they had members in the Tama district. Additionally, although I can’t speak for their organizational status, two of my acquaintances who were members in Hokkaido are still active in civic movements today.

Excuse me, the Proletarian Senki faction had at least a group of four during the 1987 anti-Crown Prince visit protest at Haneda. I also heard they had members in the Tama district. Additionally, although I can’t speak for their organizational status, two of my acquaintances who were members in Hokkaido are still active in civic movements today. @kousuke431https://t.co/sgLSqOcGzj

— Yonezawa Izumi (@yonezawaizumi) October 11, 2021

So, they didn’t come from Hokkaido after all… (murmurs).

1980: Renamed “Battle Flag Communist League (BFCL)”

A name is important, isn’t it? The current representative of Actio once said something along those lines.

Ignoring factors like the era, policy direction, and personnel might draw criticism, but it is undeniable that the Senki Faction achieved significant organizational growth after renaming itself the “Senki-Communist League(=Battle Flag Communist League (BFCL)” in the 1980s.

During the 1973 split, the Senki Faction lagged behind the “Adachi Group” (Adachi Shōkai faction, also known as the Nishida Senki Faction). However, following their July 7, 1974 rally, they restarted and by 1975–76 had slightly surpassed their rival faction in organizational strength. By the late 1980s, they had grown to the point where the authorities and the media referred to them as one of the “major factions, alongside Chūkaku and Kakumaru.“

Even seven years after the split, the existence of two “Senki Factions” and two “Senki” newspapers (organ papers) with the same name posed challenges for both sides. At gatherings like those at Sanrizuka, both factions wore red helmets and displayed banners and flags bearing the name “Senki Faction,” with only minor differences such as the lettering on their armbands. Naturally, this was confusing for newly joined members who could hardly distinguish between the two groups.

However, when it comes to disputes over names and claims of legitimacy, insisting that the other side change their name rarely resolves anything. The only practical option is to change your own name, as is often the case. Yet, unlike the transformation of “Actio,” which represented a complete change in substance, the Senki Faction sought to preserve its legacy. Therefore, abandoning either “Senki” or “Communist League” was unthinkable. After much debate over numerous proposed (and sometimes misguided) names, the proposal to rename the group to “Senki-Communist League” was adopted.

This occurred in January 1980 (to the best of my recollection) at the First All-Member Congress held in central Tokyo. Even seemingly minor details, such as whether the name should include a “・” (middle dot) or a “-” (hyphen) to link “Senki” and “Communist League,” were debated earnestly. Along with the name change, a new charter was adopted, and the organization’s structure, policies, and direction were established.

From this point onward, freed from the “curse” of being seen as merely a faction of the Bund or one half of the two competing Senki factions, the Senki-Communist League began its era of explosive growth. In June of the same year, they reestablished the Socialist Student League (SSL). This was followed by significant campaigns such as the 1980 Anti-Security Treaty and Japan-Korea Struggles in solidarity with the Gwangju People’s Uprising in South Korea, the Sanrizuka Second-Phase Airport Opposition Struggle amid the 1983 split within the Opposition League, and guerrilla and partisan struggles aligned with anti-Emperor movements. The group also achieved milestones such as transforming their organ paper, “Senki,” into a tabloid and later a broadsheet, and constructing their headquarters building, all while their mobilization power grew exponentially.

This “All-Member Congress,” where the renaming was decided, was effectively equivalent to the party congress of the Senki-Communist League. Why, then, was it called a congress instead of a party congress? It seems this was due to an underlying sentiment that a “party congress” should be reserved for the reconstruction congress of the Communist League, or the 10th Congress. (The Second Bund’s congresses ranged from its reconstruction at the 6th Congress to its dissolution at the 9th Congress in 1969, so the next would be the 10th Congress.) Similarly, the league named its theoretical journal “Riron Sensen” (Theoretical Front) after the Socialist Student League National Committee’s organ, rather than adopting “Communism,” the original journal name of the Bund.

However, there was a shared understanding that this was not about “rebuilding the Second Bund as a united front or factional coalition” but about achieving nationwide single-party growth based on the Senki-Communist League’s own development as a faction. Some individuals and factions from the Second Bund criticized this approach as “Hyūga-style Kakumaruism,” but such comments seem to stem from differing perspectives on the evaluation and situational analysis of the Second Bund.

Indeed, throughout the 1980s, there were factions within the Bund lineage that repeatedly engaged in opportunistic mergers and splits while calling themselves a “party.”

However, if they had refrained from forcing such opportunistic mergers to claim the title of “party” and instead adopted the framework of a “united front“—a form where factions with differing programs and rules come together to tackle shared challenges—perhaps their respective lineages might have been understood with greater clarity. But such unsolicited advice is unnecessary.

More than 13 years later, in August 1993, during an All-Member Congress held in Hokkaido, the decision to rename the group as the Communist League marked the first small step toward the transformation of the Senki Faction itself. Of course, no one at that time could have foreseen this shift.

Memo: The Pronunciation of “Bund” as “Bunto” or “Bund”

The abbreviation “Bunto” for the Communist League (Kyōsanshugisha Dōmei) originates as a katakana rendering of the German word “Bund” (meaning “League”).

In German, the term for “Party” is written as “Partei” and pronounced “Partei.” Among Japan’s leftist circles in the 1950s, “Partei” typically referred to the Japanese Communist Party. The First Bund used “Bund” (or League) as a common designation to contrast with “Partei” (Party). This choice appears to reflect an intent to connect the origins of Marx and Engels’ 1847 reorganization of existing exile groups into the “Communist League” (der Bund der Kommunisten) with Japan’s emerging New Left movement. (In English, this is translated as “Communist League.”)

But why do some individuals in Japan’s New Left circles occasionally pronounce “Bund” as “Bundo“?

Is it because they read “Bund” in a Romanized style (interpreting “d” as “do”)? Or perhaps they felt that “Bunto” sounded too weak (thinking the “do” ending would add strength)? Could it stem from an affinity for Lenin’s What Is to Be Done?, leading to “Bundo”? Or, was it an attempt to use “Bundo” as a critical or pejorative term, drawing a parallel to Lenin’s critique of the “Jewish Bund,” which had a federative character akin to Bunto? Or perhaps it’s just a manifestation of Japan’s typical ambiguity in adopting foreign terms? (After all, even the name of the country alternates between “Nihon” and “Nippon.”)

According to Wikipedia, “Bund” is pronounced as “Bundo” in Yiddish. Indeed, the organization referred to as the “Jewish Bund” in Japanese translations of Lenin’s What Is to Be Done?—a Jewish workers’ organization that participated in forming the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party—appears as a subject of critique. However, it seems unlikely that Japanese leftists deliberately adopted the Yiddish pronunciation specifically for “Bund.” It remains a curious phenomenon.

In any case, if you have been pronouncing or writing it as “Bundo” up until now, we kindly ask you to start referring to it as “Bunto.”

Acknowledgments: Websites and Resources Referenced

In creating the “Senki Faction Collection” website, we referred to materials such as the first and second volumes of “The Northwesterly Wind Strengthens the Party” (published by Senki-sha) for fact-checking, as well as resources and notes publicly available on the web.

To avoid excessive clutter on the screen, individual citations have not been listed. However, we would like to take this opportunity to express our sincere gratitude to the administrators of the following websites and blogs that were referenced during this process.

Likely compiled by a hobbyist with an interest in communism, this site efficiently summarizes the names and transitions of New Left factions.

Features the article “Hyūga Kakumaruism: Smash the Liquidationist Faction and Rebuild the League Revolutionarily” (dated December 5, 1973, published in Nishida’s Senki, Issue No. 340) by the Adachi Shōkai Group (Nishida Faction), which claimed to be the Central Committee (Majority Faction) of the Communist League Senki Faction. Used to reexamine their explanations or defenses regarding the 1973 split.

Referenced for details on the dissolution of the Han-ki Faction, its timing, and its relationship with Mikami Osamu.

While some entries regarding the Second Bund and Bund-related factions may contain inaccuracies, they served as general references.

Additionally, the following websites were invaluable in creating the “Hata Hata” version.

Now, here lies a bundle of photos. Holding them in your hand evokes a sense of “nostalgia.” “Where did that photo go?” “Now that you mention it, that one’s missing too.”

…Indeed, when you think about it, these are remnants of a kind. Perhaps the missing photos have already passed into the hands of someone (the rightful parties?). If so, is it better to let them decay as they are? Yet, a pang of reluctance, mixed with bitter feelings, has led to the decision to share them on the web.

Extending the life of these remnants just a little longer—true enough. However, the idea of preserving a fragment of the history of the Senki-ha on the web is also quite appealing. Hopefully, the photos that are on the path to becoming privately held treasures will join the “Senki-ha Collection”!

[August 25, 2010]

Cited from the old Senki-ha Collection homepage